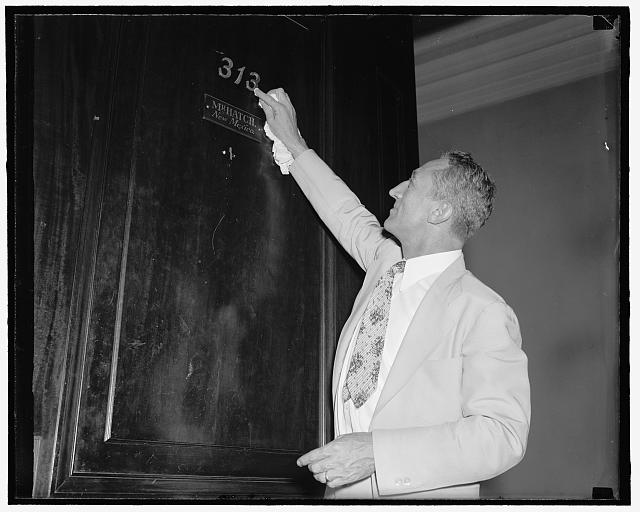

Senator Carl A. Hatch polishes up his lucky 13 office number. His Hatch Act prohibited federal employees from taking part in political campaigns. The Act was upheld against First Amendment challenges. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

The Hatch Act, an attempt to regulate corruption and possible intimidation of federal employees in the civil service by their elected supervisors, was enacted by Congress in 1939. The act banned the use of federal funds for electoral purposes and forbade federal officials from coercing political support with the promise of public jobs or funds. Sen. Carl Hatch, D-N.M., introduced the act after learning that New Deal–era government programs, specifically the Works Progress Administration, were using federal funds overtly to support Democratic Party candidates in the 1938 elections.

The act prohibits federal employees below the policy-making level from taking “any active part” in political campaigns, such as running for office in partisan political campaigns, giving speeches on behalf of partisan political candidates, or soliciting money for such candidates. Critics charge that this law also limits First Amendment rights of expression.

In 1940 Congress amended the act to include state and local employees whose salaries included federal funds. The amendment created campaign expenditure limits on political parties and contribution limits on individuals. In 1993 Congress again amended the Hatch Act to allow most federal employees to engage actively in partisan political management and political campaigns. The amendment allowed employees to express opinions on political subjects more openly. Specific exceptions to this general policy, as well as general prohibitions, are included in the Office of Personnel Management Regulations.

The Supreme Court has twice considered challenges to the Hatch Act and has twice upheld its constitutionality. The Court applied a balancing test between the presumptively valid interests of the government in regulating its employees with the individual’s interests in free speech.

In United Public Workers of America v. Mitchell (1947), the Court balanced the rights of individuals to free speech with the “elemental need for order.” In upholding the enforcement of the law, the Court deferred to Congress’s judgment regarding the amount of political neutrality necessary for federal employees. It explained that Congress was not unconcerned about its employees and that it had left “untouched full participation by employees in political decisions at the ballot box and forbids only the partisan activity of federal personnel deemed offensive to efficiency.” In dissent, Justice Hugo L. Black argued that the rights to vote and privately express political opinions were part of the broader freedoms protected by the Constitution, and he saw no reason to limit the range of freedoms for federal employees.

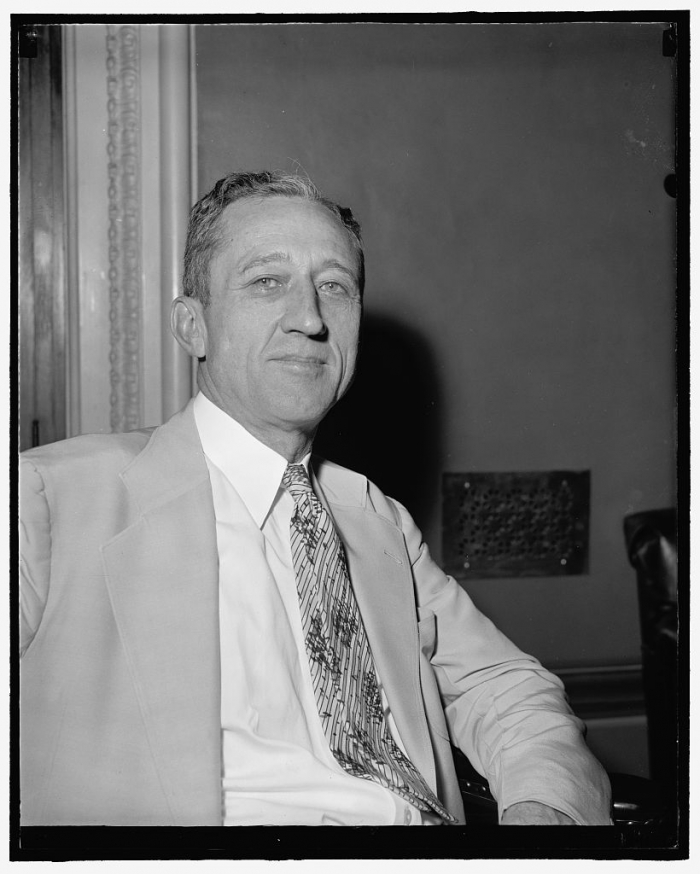

The Hatch Act, introduced by Senator Carl Hatch (pictured here in 1939), was amended many times to allow federal employees more political expression. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

The Court again reviewed the Hatch Act as amended in United States Civil Service Commission v. National Association of Letter Carriers (1973). In this case the Court overturned a lower appellate court decision and upheld the constitutionality of the Hatch Act’s ban on federal employees’ ability to take an active part in certain political activity. The Court believed that Congress had enacted a constitutional balance between the interests of an individual employee and the government-employer’s interests in maintaining limitations on partisan political activities.

The Court found that Congress used the act to avoid “practicing political justice” and also to avoid the appearance of currying federal government favor through political activity. Further, the Court explained that by limiting the political activities of federal employees, Congress protected the employees’ interests to be free from tacit coercion to become politically active. The 1993 amendments superseded this opinion, at least with respect to most federal employees.

In Broadrick v. Oklahoma (1973), the Court upheld a state law restricting the political actions of state employees. In United States v. National Treasury Employees Union (1995), however, the Court limited the scope of a ban on honoraria given to federal employees for speeches and writings. Bauers v. Cornett (8th Cir. 1989), involving an appeal by an employee of the Missouri Division of Employment Security against the director and assistant director, who had questioned the employee’s attempt to raise funds for lobbying efforts, further explains statutory changes superseding Supreme Court decisions in Broadrick and Letter Carriers.